“Human beings are at the centre of concern for sustainable development. They are entitled to a healthy and productive life in harmony with nature. Women have an essential role to play in the development of sustainable and ecologically sound consumption and production patterns and approaches to natural resource management.” (United Nations 1995: Part K, para 246)

Twenty years have passed since the passage above was written in the Beijing Platform for Action’s Critical Area of Concern, Part K “Women and the Environment”, but the central argument that women are key actors in the environment remains constant. In January, the Society for International Development-Washington, DC Chapter’s Gender and Inclusive Development (SID-GID) workgroup brought together a panel of gender, agriculture, and environment experts as a part of a yearlong series to consider: What has been accomplished under the three strategic objectives in Part K: Women and the Environment over the past 20 years? What actions does the development community still need to take? The panel included Deborah Rubin from Cultural Practice, LLC (CP), Margaux Granat of International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Eija Pehu of the World Bank and was moderated by Lisa Ronér of Land O’Lakes, Inc.

K.1: Involve women actively in environmental decision-making at all levels

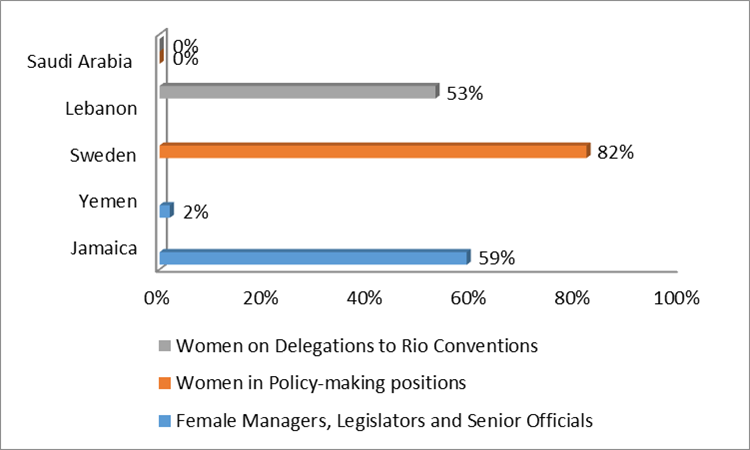

Results from the Environment and Gender Index (EGI), developed by IUCN, show a 36 percent global average participation rate for women in inter-governmental negotiations on environmental issues including climate change, biodiversity, and desertification, with significant differences across countries (Table 1). The data indicate that we still have a significant amount of work to do to ensure that women are able to reach higher levels of environmental decision-making. A 2012 review of gender mainstreaming in the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) recommended that in order to increase the number of women relative to men who hold management and decision-making positions, investments need to be made in professional development training for women, a better understanding of the constraints women face in rising to managerial positions, and the development of internal policies that support men’s and women’s child caring needs.

Figure 1: Best and worst performing countries on women’s participation

K.2: Integrate gender concerns and perspectives in policies and programs for sustainable development

Perhaps one of the bright spots of achievement, the key conventions and agreements governing international environmental efforts have integrated gender concerns and perspectives. The three Rio Conventions on biodiversity, climate change, and desertification incorporated gender and governments officially committed to implement these agreements, and monitor and report outcomes. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) now includes gender, particularly in areas concerning adaptation. Climate Change Gender Action Plans launched at the 18th Conference of the Parties of the UNCCC in Doha, Qatar in 2012 are also encouraging countries to take action on issues related to gender and climate change.

Greater attention to gender issues in environmental and agriculture programming are also contributing to fulfillment of this objective. Margaux Granat highlighted the new The Global Environment Facility (GEF) policy on gender mainstreaming (2011). GEF projects are now assessing the gender dimensions in their activities and addressing women’s roles in natural resource management and related income-generating activities. In agriculture, Deborah Rubin, Director of Cultural Practice, LLC pointed to new initiatives like the Integrating Gender and Nutrition within Agriculture and Extension Services (INGENAES) project aimed at strengthening gender and nutrition integration.

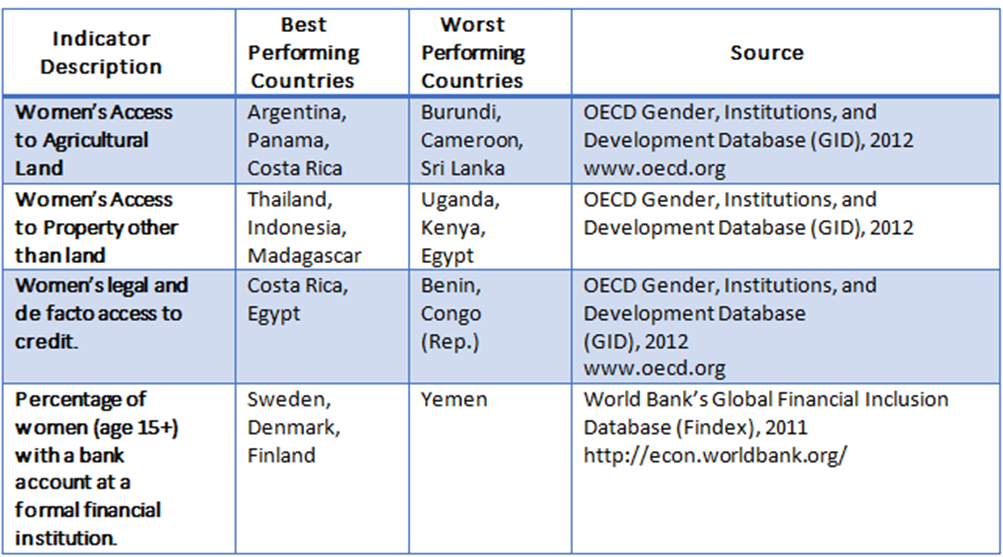

However a number of key issues remain, in particular the issue of men’s and women’s access and ownership of assets. Eija Pehu, Science Advisor with The World Bank, noted that the UN Fourth Conference on Women helped the community focus on the importance of access to land, which she called “a binding constraint” for women. Women own, operate, and access less agricultural land than men, who not only have more land but often larger land holdings (FAO 2011:23). This disparity is often tied to policies that limit women’s ability to inherit and own land. As Table 2 illustrates, women continue to lag behind men in access to property other than land, credit, and formal financial mechanisms.

Table 1: Best and worst performing countries on women’s access to assets

Additionally, gender disparities persist in education and training in disciplines like science, technology, economics, and agricultural persist. The Agricultural Science & Technology Indicators (ASTI) report Synthesis of the ASTI–award benchmarking survey on gender-disaggregated capacity indicators highlighted by Eija Pehu, found a slight increase in women’s participation in agricultural research and higher education between 2000-2001 and 2007-2008 from 18 percent to 24 percent. While slight increases in women’s participation in these technical areas have been documented this remains a challenging area in need of greater attention.

K.3. Strengthen or establish mechanisms at the national, regional, and international levels to assess the impact of development and environmental policies on women

In recent years there has been an increased investment in data collection and analysis on a number of fronts. Investments have been made to capture more sex-disaggregated data and use this to analyze how gender-based constraints limit our ability to reduce poverty, increase production, and protect the environment. The reports below are examples of how data has been used to improve our understanding of these constraints:

IUCN’s Environmental Gender Index piloted in 2013 includes sex- disaggregated data on livelihood, ecosystem, gendered rights and participation, governance, gendered education and assets, and country reported activities for 72 countries. Read the results of the 2013 pilot here.

IUCN’s Environmental Gender Index piloted in 2013 includes sex- disaggregated data on livelihood, ecosystem, gendered rights and participation, governance, gendered education and assets, and country reported activities for 72 countries. Read the results of the 2013 pilot here.

The Women’s Empowerment and Agriculture Index (WEAI) includes data on indicators related to women’s participation in decisions about agricultural production, decision- making power over productive resources, control over use of income, leadership in the community, and time use.

The Women’s Empowerment and Agriculture Index (WEAI) includes data on indicators related to women’s participation in decisions about agricultural production, decision- making power over productive resources, control over use of income, leadership in the community, and time use. The World Bank’s “Levelling the Field: Improving Opportunities for Women Farmers in Africa” (2014) report synthesizes data on gender gaps in agricultural productivity in Ethiopia, Malawi, Niger, Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda.

The World Bank’s “Levelling the Field: Improving Opportunities for Women Farmers in Africa” (2014) report synthesizes data on gender gaps in agricultural productivity in Ethiopia, Malawi, Niger, Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda. The FAO’s State of Food and Agriculture (2010-2011) focused on Women in Agriculture: Closing the gender gap for development. This report includes country-level data on gender gaps in land, livestock, farm labor, education, information and extension, financial services, and technology.

The FAO’s State of Food and Agriculture (2010-2011) focused on Women in Agriculture: Closing the gender gap for development. This report includes country-level data on gender gaps in land, livestock, farm labor, education, information and extension, financial services, and technology.

What do we still need to do?

Over the past 20 years, significant progress has been made to integrate gender into international and national policies on the environment and agriculture. Databases with sex-disaggregated data developed by leading institutions have deepened the existing knowledge on key differences between men and women. This data will be essential for understanding progress over the next 20 years. While progress has been made to fulfill the commitments in the Platform for Action, panelists noted a number of ways donors, international organizations, and national governments can support men and women to meet 21st century environmental and agricultural challenges:

- Engage and accept men and boys to advance progress as ‘change agents’;

- Increase the number of women studying and working in the agricultural sciences;

- Sustain commitment to understanding gender dynamics of asset ownership and control and access to services; collecting sex-disaggregated data (particularly in the environmental sector); and, increasing women’s voice and agency;

- Incorporate gender issues into the climate smart agriculture agenda;

- Explore and incorporate new development approaches to link nutrition; climate smart agriculture; rural jobs and entrepreneurship; the private sector; and ICTs into agricultural and environmental work.

Learn more about the yearlong series: Beijing+20: What Does Meaningful Progress Look Like?:

Learn more about the yearlong series: Beijing+20: What Does Meaningful Progress Look Like?:

http://www.sidw.org/2015-sid-gid-discussion-series

Join us on March 25 for the third event in the series Beijing+20: What does meaningful progress look like in addressing issues for the “Girl Child”? Looking closer at linkages between Child Marriage and Education.

Follow us on Twitter: #SIDwGID

This blog post was developed by Cultural Practice, LLC and World Learning, Co-Chairs of the Society for International Development-Washington, D.C., Gender and Inclusive Development Workgroup.