What do food and gender issues have to do with each other? Quite a lot. But you might not know that without using innovative evaluation methods that allow local voices to take center stage. In a recent TOPS-funded evaluation of a food security project with Lutheran World Relief (LWR) we found, as Monitoring and Evaluation Manager Wendi Bevins put it, that all the seeds and technology were important, but gender integration was what made the agricultural improvements stick. Nowhere was this seen more strongly than in the stories and photographs of the local men and women who participated in the food security project and project evaluation led by LWR and Cultural Practice, LLC (CP).

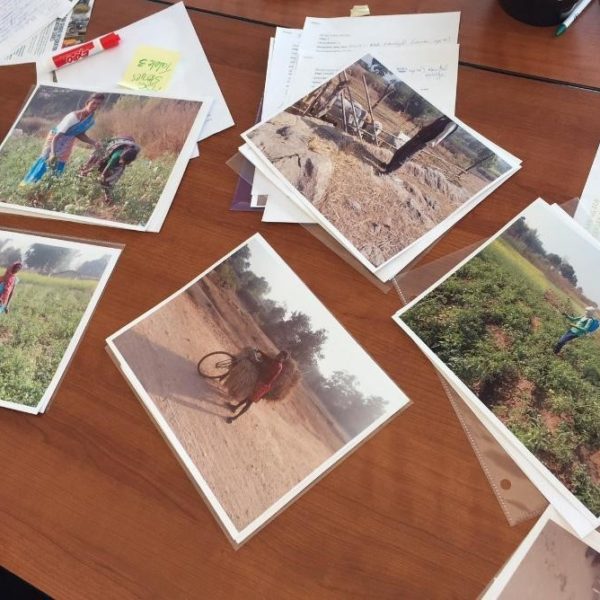

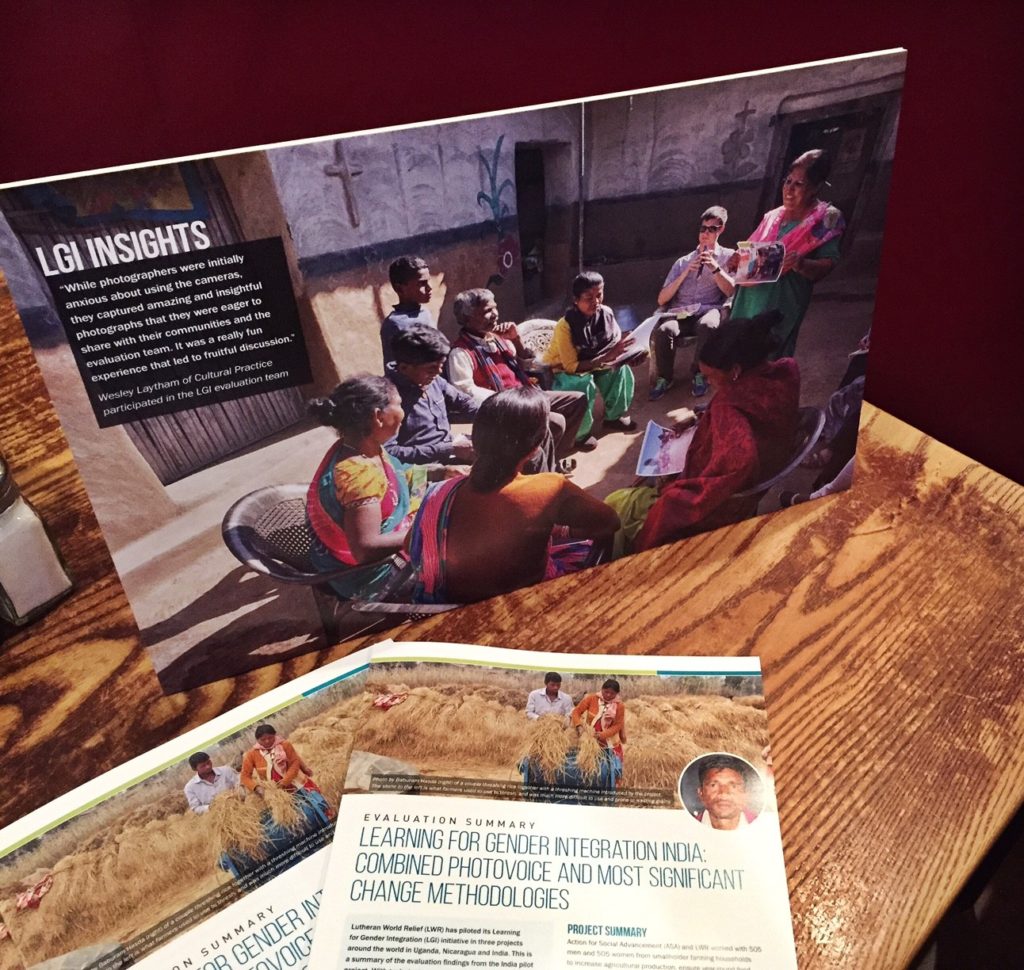

On a spring evening, we gathered to showcase the evaluation reports and the photobook that were built on the photos taken by participants. The photos and reports came from the evaluation of the Learning for Gender Integration (LGI) Initiative pilot projects. The goal of these projects was to train staff to ensure that men and women had equal opportunities to benefit from LWR’s support. The projects were tailored to three different country contexts: Nicaragua, Uganda, and India.

CP and LWR used the opportunity to develop and a test a combination of two participant-led evaluation methods: PhotoVoice (PV) and Most Significant Change (MSC). These two methods had never been brought together before. CP wanted to evaluate whether gender relations had changed, and if so how and why. By combining these two methods, one using photography, one using stories, CP could capture that change. While PV and MSC shouldn’t be the only evaluation tools, they can help illuminate changing social relationships with a sensitivity to context that is not always captured by other techniques.

With PV, evaluators gave out cameras to participants and asked them to photograph the biggest change that the food security project had brought to their community. This placed the power of evaluation straight into the participants’ hands. As one project partner said, “there is a lot of power in witnessing people exercising their own agency and telling their own stories.”

The PV technique is a way to bring men and women participants into the actual data analysis and into a more “equitable dialogue”, says Debbie Caro, Co-Director of CP. Traditional evaluation methods are often seen as extractive, but with PV the process itself empowers participants who are trained to use cameras, take photos that are significant to them, and bring them back to the group to discuss and ultimately display for the community. In Nicaragua one man took a photo of his wife watching television; it was significant because before the project, she was too burdened with work to have free time. Changing gender roles were captured in several of the photos: in Uganda, there was a photo of a man carrying firewood, and in India of women and men working together in the fields. As the photographers explained why they took these photos, LWR and CP learned about the changes that were occurring among work roles and what they meant to participants.

With the project staff from the local implementing partner organization, CP and LWR used a method called Most Significant Change (MSC), asking staff to tell stories that showcased the changes brought about by the food security project. They then discussed themes and voted on the most important change that they witnessed. MSC is a valuable tool to capture the impressions of staff that are not documented in other sources of data.

After the MSC and PV evaluations, the staff and participants came together with the community to share the changes they had witnessed and all that they had learned. Bringing PhotoVoice and MSC together in the same space for an exchange was a brand new innovation. This exchange allowed the power dynamics to level out between literate/educated staff and project participants who were often less-educated and let project participants be part of the learning process along with staff. It also gave evaluation teams a chance to understand the relationship between community and staff, and see what both groups thought about the issues.

Main Findings

These innovative evaluations, alongside traditional quantitative monitoring data and endline surveys, found similar patterns in each country: food production rose! Alongside the rise in food production, gender roles changed to varying degrees among participants. In every country, participants brought up the differences between men and women in terms of knowledge and decision-making. In Uganda, the data showed that resources and decision-making were shared among the family more after the project. The same was found in Nicaragua, where more women were included in household decision-making. Ideas around masculinity changed at the Nicaragua site, as men became more likely to engage in household chores – something that many participants, especially women, captured in their photographs.

In India, while some decisions were still mostly made by men, at the end of the project other decisions were shared among husbands and wives. Men and women’s lives were less separate than before the project: men no longer migrated since increased production meant they were needed on the farm. This could have translated into increased control by men, but since women had been trained in the new farming technology and controlled the financial resources via their self-help groups, the decision-making was more equal. In general, there was a raised self-awareness of their own gender roles and how it affected their lives across the three countries.

Highlights of training

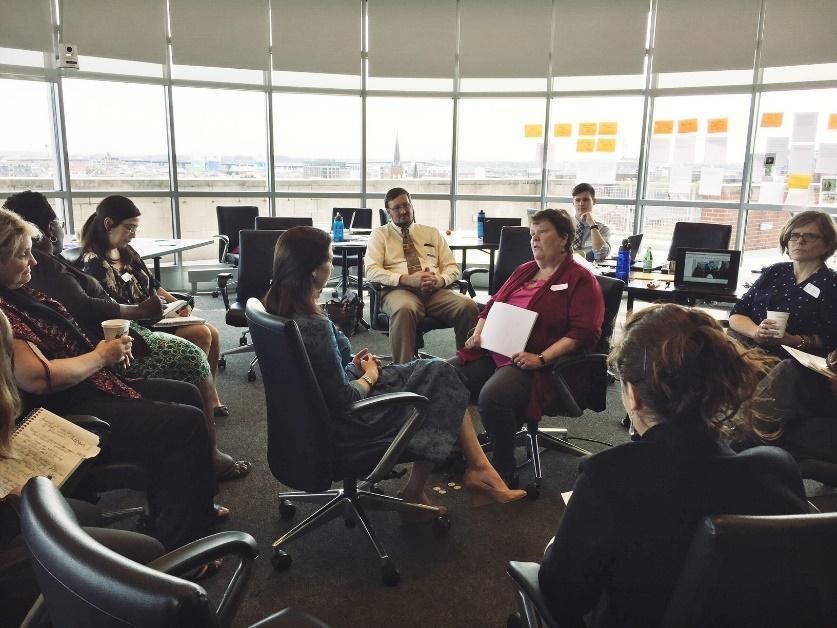

To share these innovative evaluation methods, LWR and CP held a training for the joint MSC and PhotoVoice methodology on a sunny Thursday in Baltimore. The workshop participants hailed from different parts of the world but shared their passion for international development and gender equity. As they listened and participated in the evaluation methods, they soon noticed what Debbie Caro made sure to explain – that when using MSC and PhotoVoice, social and cultural context had to be taken into consideration, to be able to interpret what people say and understand what it means. The workshop participants asked insightful questions: What did we mean by change? Were staged photos showing aspiration or reality? What about logistics, how did you choose participants and how did you train them?

Using PV and MSC allowed evaluators to reveal changes in gender relations that might not have been uncovered otherwise, digging through the local context and power dynamics to garner the real changes in people’s daily lives. Moving forward, other evaluators can use these methods to dig deeper into the impacts of their projects by putting control into the hands of the participants.

Photo Credit: Mary Ellen Dingley