This past year Cultural Practice, LLC (CP) evaluated three Lutheran World Relief (LWR) projects in India, Uganda and Nicaragua. These three projects were pilots for the Learning for Gender Initiative (LGI) and focused on raising agriculture production and reducing gender gaps.

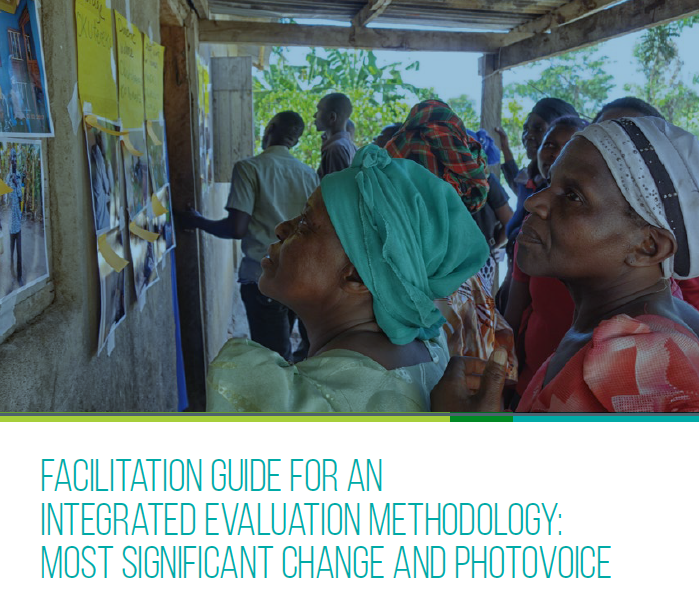

CP led an evaluation of these pilot projects using an innovative combination of two qualitative methodologies: Most Significant Change and PhotoVoice. The team tested out these participatory methodologies, learning “on the ground” lessons about the value of the data gathered and best practices in implementation. LWR and CP recently published the facilitation guide for other organizations interested in using these methods. Check out the guide and read on to find out how your organization can use these methods in your own evaluations!

Basic definition of methods

Most Significant Change (MSC) is a means for generating and gathering stories of change resulting from a project. Participants share stories in response to a question and decide through discussion which story showcases what they view as the most important change.

With PhotoVoice (PV), data is collected via photography and oral storytellingAfter the photos are collected, participants share descriptions and discuss interpretations of the photos.

In both methodologies, participants organize their stories and photographs into thematic categories during the discussion. Capturing this discussion provides evaluators with valuable information about how participants view the changes in response to the chosen evaluation question. In the case of the LWR model projects, PV was used with project participants and MSC with local staff. Facilitators then brought the staff and participants together to share their stories and photos, a combination that had not been utilized before.

Why Most Significant Change and PhotoVoice?

These two methods were chosen as a reaction to the normally imbalanced power dynamics between evaluators and project participants. They are a means of putting the power of both data gathering and data analysis in the hands of participants. (You can read more about this in our past blog.) Both PV and MSC close the power gap by allowing implementing staff and participants to collect and synthesize the data themselves. PhotoVoice also empowers community participants to express their findings publicly, thereby also decreasing the power differential between community participants and implementing staff.

To assess the LWR projects, the facilitators brought the staff using MSC and the project participants using PV together for a final discussion, leveling the playing field between staff and participants, and allowing for a more nuanced analysis. This also allowed for a reflective discussion about change and impacts between the project communities and the implementing staff which does not occur after many projects.

These discussions, and allowing the evaluation to be participant led, provides different data than your average evaluation. PV and MSC address the methodological gap of the power dimension and are an important part of a larger gender and evaluation toolkit.

Complexity-aware methods like MSC and PV are designed to pick up on the deeper interaction of context and relationships that other methods might miss. What has occurred within the gender and power relations in response to new agricultural and nutritional practices? Rather than focus only on planned outcomes, such as “Did farm family incomes rise?” complexity aware methods catch the unplanned outcomes, the changes that may occur as “side effects” of the stated goal such as “How did women’s greater involvement in decision making affect men’s and women’s expenditures and investments?”. These methods allow you to get a better handle on the process of change. When participants tell their stories in a chronological fashion you can reach not only what had changed but also how it came about.

However, for many complexity-aware evaluation methods, the evaluators and project staff control the data collection and analysis, which gives a different set of data than would be found if participants were in control. When evaluators are in full control of the agenda, they might gather only what is important to them, and miss what is important to the participants. To shift the balance of power, participants must be put in control of both the implementation of the evaluation and the assessment of the data. PV and MSC give participants the power to concentrate on their priorities. Not only did they allow participants to gather the data, but they also analyzed it themselves, deciding on aspects such as the domains to use to categorize the shared stories. This is in comparison to many participatory methods which extract data and take it away to analyze elsewhere. One woman participant in Nicaragua said: “I liked this process very much, because we were included, we never had an evaluation like this before”.

MSC and PV can give useful data on the participants’ priorities and the change process.

In terms of the LGI pilot projects, MSC and PV were able to capture change in ways traditional evaluation methodology might not have been able to. Many answers provided by participants about change were not in the project design, and setting evaluator-led indicators may have missed them. A regular interview with participants, rather than PV, within the same time limitations, may have gotten less information as it would have been interviewer led rather than participant led. Interviewing might lead to learning how the project was meaningful to the evaluator, rather than how it was meaningful to the participant, which PV was able to uncover. Above and beyond the photos from PV and stories from MSC, the larger discussions between everyone were key to understanding the enabling environment for improved production and gender relations.

In every site, participants brought up the differences between men and women in terms of knowledge and decision-making. An example from India shows how these methods captured the process of change: new technology was introduced via the women’s groups in Indi while the men were away from home working. When the men returned, they were trained on the technology by the women. During discussions, the facilitators found that the men identified indirectly with the women’s groups their wives were part of, which is uncommon! This process of change came out strongly by allowing participants a greater voice.

Basic Steps to Facilitate MSC and PV

Most Significant Change:

- Train staff in use of MSC and how to identify an MSC story

- Staff develop and share stories in response to an evaluation question, which they arrange into themes

- Staff develop criteria and use it to select the story that reflects most significant change

- Train staff in validating stories through drawing/listening exercise

- Send them into communities to validate them

PhotoVoice:

- Community session with everyone: explain PV and gather stories of change

- Just photographers: teach them how to use camera

- Participants go out with cameras (for a week or so) to take 20 photos of change in response to an evaluation question

- In discussion with evaluators, participants pick 5 photos that represent the most important change to them

- The PV participants gather to discuss their photos and the stories behind them – gathering themes and comparing perspectives of men and women. They pick 1 or 2 photos per theme.

At the completion of both methodologies, the staff and participants are brought together for a combined presentation and discussion, where they display their photographs and stories.

Basic structure of combined workshop:

- Gallery Walk

- Small Group Discussion about Photos and MSC Stories

- Rating of Stories and Photos

- Plenary presentation and discussion of small group work and of selected stories

- Evaluation/Reflections on the Process and Findings

The final step in the evaluation process is comparing the qualitative data collected during fieldwork with baseline, endline, and monitoring data collected by the project. This triangulation allows the evaluation team to explore qualitative data in more depth and helps to establish trends within the country or across projects.

MSC and PV can also be built into the design of the project at phases other than final evaluations, i.e. at the beginning stage to conduct a needs assessment.

Lessons Learned with the LGI Pilot Projects

PV and MSC were useful in capturing the process of change in the LGI projects. In several stories the participants mentioned what made them decide to do something differently – PV captured that “aha” moment.

Some lessons were also learned while facilitating PV and MSC, including:

- The methods took 3 days of people’s time, which was very hard on some of the women

- You must be selective in choosing photographers, to make sure to not reinforce community power dynamics.

- In general, more information on community dynamics is needed to choose how to delegate tasks (ie who invites people to attend the gallery walk).

- Separating men and women in initial meetings allows women to speak more freely

- Setting up the final exhibit as a gallery walk rather than individual speeches keeps the audience from getting bored.

- It’s a good idea to gather opinions from participants on whether they enjoyed or found useful the PV process

- It would be useful to know more about the local context before the evaluation so you can understand what people are referring to.

One exciting aspect of PV and MSC is the potential higher likelihood that changes will be more sustainable; that if participants have been part of an evaluation with their voices valued, publicly discussing and acknowledging the changes around them, perhaps the changes are more likely to be permanent. Of course, these methods should also be combined with other types of data such as baseline/endline comparisons, focus groups, and interviews as part of a comprehensive evaluation.

Blog written with input from Deborah Caro. Photo credit Deborah Caro and LWR Facilitation Guide.