The U.S. Global Development Lab (Lab) and the Bureau for Food Security are collaborating in an effort called “Digital Development for Feed the Future” (D2FTF) with the goal of demonstrating that digital tools and approaches can improve cost-effectiveness and better development outcomes in food security and nutrition programming. This blog features the case study on the International Crops Research Center for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT).

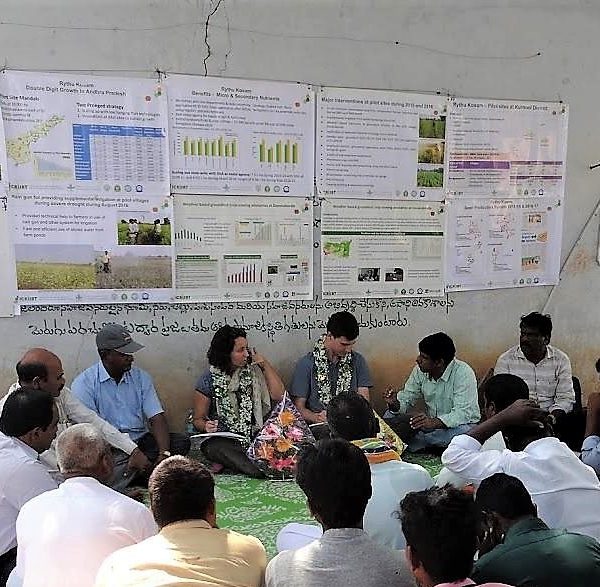

In December 2017, I met with farmers from Swakrushi Farmer Producer Organization (FPO) in Peechara, Telangana—a three-hour drive from Hyderabad, India—about their use of digital tools, primarily mobile phones, in their farming businesses. Over and over again, the farmers described how they felt they knew “nothing,” or very little about how to improve their crops, connect with markets, or address a pest disease.

Nowadays, men and women farmers are in a different place because of digital tools like the free online platform Kalgudi, which connects producers, traders, researchers and other agribusiness actors. Swakrushi farmers described using Kalgudi to find new markets for vegetables, secure buyers, or learn new production practices. These farmers received recommendations and interacted online in Telugu, their local language—allowing them to engage more meaningfully online.

Kalgudi is one of a number of initiatives being supported by the International Crops Research Center for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), a CGIAR center based in Hyderabad, India that works across Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia to reduce poverty, hunger, malnutrition, and environmental degradation in the dryland tropics. Since 2014, the organization has been transforming itself to fully embrace digital agriculture. Across the organization, leadership and researchers alike see digital development as the future for their work from, crop breeding to implementation, and a critical element of fostering a 21st century agricultural transformation in India and elsewhere.

ICRISAT uses a range of digital agriculture tools and approaches to help forge effective partnerships, increase efficiency, and deliver better services to farmers. For example, the Sowing App and Intelligent Sowing Advisory Tool (ISAT) provide farmers with simple information about what to plant and what management practices to adopt. Farmers receive SMS messages with recommendations based on an analysis of their crops, soil, and weather conditions. Farmers that follow this advice have improved yields by up to 30% and increased income by up to 20% for the Sowing App and ISAT respectively.

During my trip, farmers explained how they found SMS messages helpful, and feel more confident in their decision-making abilities. Digital tools like the LeasyScan and HarvestMaster rapidly and accurately measure large amounts of physical plant characteristics and are changing crop improvement programs at ICRISAT. The measurement standardization of data improves the accuracy and speed with which researchers can develop improved varieties, while reducing costs.

While ICRISAT works across South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, India offers a great analogue for many countries in which ICRISAT works. Its large number of farming families, estimated at 137 million, and degraded environments drives a mandate to rapidly develop cost-effective and impactful solutions to agricultural development. Unlike other countries however, India’s technological landscape offers the additional opportunity to test how digital technologies can accelerate the discovery and delivery of research outputs. To leverage this local expertise, ICRISAT created the iHub, an incubator that brings technology innovators and agricultural researchers together. Through the iHub, ICRISAT is helping create local solutions to challenges facing smallholder farmers and other value chain actors. With the support of several state governments, many of ICRISAT’s digital tools have been piloted in conjunction with public extension programs and agricultural universities.

Many of ICRISAT’s digital interventions highlighted during my trip are nascent, yet they show great potential for sustainable development. Demand by farmers and partners alike demonstrate the promise offered by many of these tools. Though the digital divide is smaller where ICRISAT is promoting these digital tools, onboarding India’s entire rural population remains a challenge. Scaling these approaches across India will take time and introducing them into new countries may require significant advances in the digital landscape. ICRISAT is already working to bring digital agriculture to other Sub-Saharan African and South Asian countries. It has an international footprint and is finding ways to promote digital development throughout its entire portfolio of programs. The next several years will show how the investments ICRISAT is making in digital agriculture can help farmers achieve better agricultural outcomes.

A full case study featuring ICRISAT’s work can be found here.

Header photo credit: Sudi RaghavendraRao (ICRISAT), 2017.